in Polish/po polsku

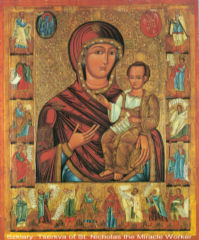

The most beautify icons in the Polish collections

The requirements made of the icon by theology generated a specific artistic language and workshop practice quite different to what was current in Western art. The greatest importance was attributed to the figures of the saints depicted in the icons and their faces, which were to be free of the earthly reality, subjected to apotheosis and uncorporea , with no lifelike gestures, always in a frontal arrangement and with the preservation of symmetry. Their eyes were to be directed at the observer, which was to facilitate the establishment of contact through prayer. On the other hand in the icons presenting hagiographies (life-stories of the saints), the episodes from their lives and miracles would be separated off from the central figure by a definition of the time and space in which these events occurred. As opposed to the central figure, the hagiographic presentations would not correspond to the time and place of the praying observer; they would be narrative and illustrative in character. This dichotomy in the hagiographic icons would be augmented by the kovcheg border, marking off the concave, deeper level of the central panel, and its far-reaching consequences for the icon's structure and composition. The peripheral scenes could contain elements of architecture and landscape which would be much more elaborate than what might have occurred in the central panel if the iconography of the figure portrayed called for it. Nevertheless the landscape elements in icons would always be restricted to the hills and palat idiosyncratic of the icon, so unrealistic and deformed as to have an existence restricted merely to the micro-cosmos of the icon, and meaningless or even unidentifiable if removed from it. If any depiction of reality is to be seen in the icon, then it can only be of the evangelical reality, and in the context of the whole icon, the individual parts of which should always be subordinated to the whole entity. The deformation of its landscape and architectural items was an outcome of the application of the "inverted perspective of meaning," whereby the size of the figures and backgrounds portrayed represented their relative status in terms of significance. Meaning perspective also affected the relative magnitudes of the objects shown in an icon, which would be limited only to those absolutely essential . They would diminish in size the further away they were from the center of the icon. The architecture would be shown both from within and from an external view, the latter of which tended to be located in the icon's peripheries. Such treatment does not give a full presentation of the architecture; it delineates the boundaries between the sensual and extra-sensual world; but it also eliminates the need for frameworks, since the external views of the architecture provided the natural frames for the icon. The well-nigh-ubiquitous gold in the icon, its "standard fixture," shows an extra-sensual reality. The gold of the icons is treated as a representation of the glory of the martyrs, a reflection of the divine energy and a paradise unblemished by worthlessness or sin. Gold would also mark out the icon's internal boundaries. The use of gold as an outline for the robes of the saints and the chrysography (gold patterning) of the robes themselves indicates the fact that the saints dwell in the "better world." The colors of the icons are few, and their meanings symbolic. A characteristic feature of icons is that they have no play of light and shadow. Neither do they show the source of the light in them, since it is this light that builds up the icons themselves.

Icon theology was received with general enthusiasm by the researchers, recipients, and artists themselves, who saw the transfer of the rules of icon theology to contemporary religious painting as a means to save icon art. Reference to icon painting was envisaged above all as an opportunity for the restoration of a spiritual dimension to modern religious art. However, the theology of the icon also has some inherent dangers for the true interpretation of icons. It is a totally historical approach, which ignores the existence not only of a general development model and socio-political context in which the icons emerged, but also denies the existence in Orthodox Christian art of a beginning, a growth, and a decline, not to mention its major changes. But such changes did occur, although they were never revolutionary in character. Furthermore, icon theology emphasizes the supra-aesthetic values in icons, and subordinates the artistic and aesthetic qualities to this, often depreciating them. But it is enough to cast a glance at the icons to tell that the quality of the art in them varies. Some were made by highly talented masters, others by mediocre painters. Some come from the leading centers, others were made in provincial workshops. Moreover, in many cases the stylistic qualities of the various icons are easily discernible, and they may be ascribed to particular schools, workshops, and in a few instances even to individual, outstanding artists. On the whole, however, within the context of the mass demand for these "works of art" unknown elsewhere, there was a general tendency to maintain the standard of their quality at a certain artistic level. This was a consequence of the belief that an icon's quality enhanced the accessibility of the spiritual qualities it carried. Despite the simplicity and clarity of the means of expression applied in icons, which were to be readily decipherable to all, and their apparently limited iconographic repertoire, there can be no doubt that the icon painters mastered the art of communicating even the most profound and complex meanings in the Christian faith to their recipients. There were many factors that influenced the evolution in the iconographic repertoire and in the art forms used. Some of the main factors of change involved changes in the liturgy, which generated new subjects, although the iconographic schemata would always be in line with the traditional principles. Another important factor was the social status of the founders of icons, and the proximity or remoteness of the leading centres for icon art. One of the problems which is more relevant to icons than for other works of art is the manner of reception, since a fully aware perception of icons implies a progress into the world of an art full of meanings and exerting a stronger impact than other works of religious art. But such a mode of reception is also determined by factors external with respect to icons, and received in a different manner in a church, where there is a large concentration of them, generally from different periods, and where they are in their natural setting; and in a different way if displayed in

galleries, museums, antique fairs; or in a different manner still in reproductions. Despite the fact that there may be interaction between icons and worshippers apparently only in the setting of churches or private home, where icons are allocated a special place, the power of their emotional impact, even when lodged in an environment artificial for them, is evidenced by a fact registered by the mass media - the sight of women kneeling and praying before an icon of the Blessed Virgin of Vladimir on display in the Tretiakovskaya Gallery in Moscow. This continuity, the long-lasting cult of the icons, the major forms of which were developed already in 4th century Byzantium, has come down to the present day well-nigh unchanged, despite the transformations in culture. It is a result of the fact that icons were an indispensable constituent of both private and public life. They were with Eastern Orthodox Christians at all the most important events in their lives, from birth to death. They were founded and venerated by the entire community, irrespectively of social status. They were an element of social integration in public life, since the veneration accorded icons and the feasts and rituals associated with them was a communal cultural dimension that united the elite groups with the rest of society. Understandably, the reception and cult of the icons was not a static phenomenon, and its exact character would often be imposed by the ruling c asses and exploited for political purposes. Some icons were more popular in certain periods, others less so; often the cult of particular icons would be local. But two kinds of icons which were always among the most popular were the acheiropoeitos or nerukotvornye, "not made by human hand," alongside those attributed to St. Luke. This meant the Mandillion and the Hodegetria. The introduction of iconostases in the churches and their development with the propagation of their rows of icons meant that the worship of icons acquired an even more collective and regular character, although at the same time it was deeply personal.

The theology of the icon has given a very clear formulation of the differences between the painting of the Eastern Church and the Roman Catholic religious art. For the former icons were the only admissible objects of veneration. However, already in the late Byzantine period East encountered West. Although it was a hostile encounter, in the realm of art it brought visible changes. We may say that in this first period the West had much to thank the Byzantine art for, as the icons which were brought in to the West, especially to Italy, not only helped to create new types of images, but above all they were treated as images endowed with a miraculous power. However the reaction of the West upon the East from the period of the fall of Byzantium proved far more painful, sometimes far more destructive for the icons. Russia was the only independent country to continue the Orthodox traditions, both in the theology of the icons and in the painting of the canonical icons. But even here from the mid-17th century onwards the impact of Western art was stronger and stronger. This gave rise to the co-existence of a religious art Latinized both in form and content with the traditional icon painting. Meanwhile in Greece, Crete, and also Central Europe (modern Poland, Western Ukraine, Slovakia, Hungary, and Rumania) the influence of Western art first resulted in the abandoning of the gold background, which was replaced with other colors, a more naturalistic approach to the figures and robes, the introduction of Renaissance architecture, and the removal of the kovcheg. The use of Western, chiefly Dutch or German pattern-books became a common practice. This implied the introduction of iconographic subjects which were wholly alien to the art of the icons. The formal impact led to a complete change of style and composition in the representations - to an imitation of reality in the portrayal of architecture and landscapes entirely out of character for the icon theology, to the use of superficial color, converging perspective, external illumination, diversification in the emotional states depicted in the figures, inappropriate attention to anatomical details, and superfluous motifs of decoration in a Baroque manner. The reproduction of visual realities in tabular icon art eventually led to the deprivation of that church art of the timelessness so rigidly adhered to in the canonical icons. Instead the events presented acquired the attributes of transience, and evangelical reality ceased to be the mandatory form. A very significant milestone on the road to the stripping of the icon of its sacred character was the repudiation of the theologically necessary rule of inscribing icons with identifying captions. The change in the function and form of the iconostases gave rise to the introduction of sculpture, which had never been practised in icon theology. And when graphics were brought into religious worship, its mass-produced character made the images reproduced on paper forfeit their attribute of uniqueness, which is what has always marked out, and still marks out icons. The influence of Renaissance aesthetics led to a change in the status of the artists, who now documented the idea that their works were an outcome of their individuality in the form of a signature on their paintings, along with inscriptions identifying their patrons and the exact date when a particular work was made, in spite of the loss of so many characteristics of the icon, the "mixed" painting is distinctive as a type that grew up on a cultural border. The order of the icons we present here has been chosen in accordance with the meanings of its subject-matter and the hierarchy ascribed by icon theology to the various figures and representations. In compliance with that hierarchy, the album opens with the icons of Christ, the acheiropoetic icons first; followed by representations of the Holy Trinity; of the Deesis group; and then by images of the Mother of God. Next come the narrative representations, especially the icons illustrating the twelve great feasts of Eastern Christendom showing the main events from the lives of Jesus and Mary as described in the Gospels. Then there are the images of the Patriarchs, Prophets, Archangels, Evangelists, Apostles, Fathers of the Church, Bishops, Holy Martyrs, Soldier Saints, and other Saints. The album closes with representations of the Last judgement, which contain the hope of the life to come.

The icons reproduced in this album come from two museums in Sanok (Muzeum Historyczne and Muzeum Budownictwa Ludowego), whose icon collections are the best in Poland and among the finest in Europe.

Barbara Dab-Kalinowska

Reference works

R. Biskupski, Ikony w zbiorach polskich [Icons in Polish Collections], Warszawa,

1991.

B. Dab-Kalinowska, Ikony i obrazy [Icons and Pictures]. Warszawa, 2000.

I. Yazykowa, Swiat ikony [The World of the Icon], Polish translation by H.

Paprocki, Warszawa, 1 991.

L. Uspienski, Teologia ikony [The Theology of the Icon], Polish translation by M.

Zurowska, Warszawa, 1991.

Professor Barbara Dab-Kalinowska is an art hislirian and an eminent Byzantinofogist. She has published numerous books and papers on Russian and Ruthenian art, and on the methodology of art, including Miedzy Bizancjum a Zachodem. Ikony rosyjskie XVII-XIX wieku [Between Byzantium and the West. 17th -19th Century Russian Icons], Warszawa, 1990; Ziemia. Pieklo. Raj [Earth, Hell, Paradise], Warszawa, 1994; and Ikony i obrazy [icons and Images], Warszawa, 2000. Since the beginning of her academic career she has been associated with the Institute of the History of Art at Warsaw University.

Local Links:

Document Information Document URL:http://lemko.org/books/ikony/index.html

Page prepared by Walter Maksimovich

E-mail: walter@lemko.org

Copyright © LV Productions

E-mail: webmaster@lemko.org

|

|

LV Productions c/o Walter Maksimovich 3923 Washington Street, Kensington MD 20895-3934 USA |

Originally Composed: December 25th, 2002

Date last modified: